What Happens When All 21 Million Bitcoins Are Mined?

It’s one of the biggest questions in crypto: what happens when the very last Bitcoin is mined? The network is designed to hit its hard cap of 21 million coins sometime around the year 2140. When that day comes, the system will keep running just as it always has, but with one fundamental change.

Miners will no longer receive freshly minted Bitcoin—the block rewards—for their work. From that point forward, their entire income will come from the transaction fees users pay to get their transactions included in a block. This isn’t some future patch or an emergency fix; it’s a core part of Bitcoin’s original design, a slow-motion economic shift that’s been in progress since day one.

In short, the network was built to eventually stand on its own feet, funded entirely by its users.

The Inevitable Shift in Bitcoin’s Economics

The 21 million coin limit is arguably Bitcoin’s most famous feature. Satoshi Nakamoto built this into the protocol to create true digital scarcity, mirroring the finite nature of precious metals like gold. This hard cap is what prevents the endless inflation we see in traditional fiat currencies, where central banks can effectively print money without limit.

But what actually happens when we hit that ceiling?

This isn’t a Y2K-style event where everything suddenly breaks. It’s a gradual, completely predictable transition. The system was always meant to slowly phase out the block rewards, weaning miners off them and onto a sustainable fee-based model.

The goal is to ensure miners always have a powerful financial reason to keep securing the network. Their job—validating transactions and adding them to the blockchain—remains essential. The only thing that changes is how they get paid for it.

From Dual Income to a Fee-Only Model

Right now, a miner’s revenue comes from two places: the block subsidy (new coins) and the transaction fees from the block they solve. Every four years, the subsidy gets cut in half, and as we inch closer to 2140, it will eventually dwindle to nothing. Fees will be all that’s left.

This transition is the bedrock of Bitcoin’s long-term security model. For the network to remain secure for centuries to come, a healthy, competitive fee market must exist to make up for the disappearing block rewards.

Let’s break down how this economic model evolves.

A Quick Comparison: Before and After 2140

The table below offers a snapshot of how Bitcoin’s core mechanics will change once all 21 million coins are in circulation.

| Network Aspect | Current State (Block Rewards Exist) | Future State (Fee-Only Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Miner Incentive | Newly created Bitcoin (block subsidy) plus transaction fees. | Transaction fees paid by users only. |

| New Coin Creation | A set number of new bitcoins are created with each block. | No new bitcoins are ever created. |

| Supply Dynamics | The total supply is inflationary, though at a decreasing rate. | The total supply is fixed and becomes deflationary as coins are lost. |

| Security Budget Source | Primarily funded by the issuance of new, valuable coins. | Entirely funded by the demand for block space from users. |

The key takeaway is this: The end of Bitcoin issuance isn’t the end of the network. It’s a planned graduation to a self-sustaining economic model where security is paid for directly by its users, not through the creation of new currency. Moving to a system driven purely by market demand is the ultimate test of Bitcoin’s design.

The Slow Countdown to 21 Million

Reaching the 21 million Bitcoin cap won’t be a sudden cliffhanger; it’s the quiet, predictable finale of a century-long process baked into the code. The entire journey is governed by a mechanism called the halving, which works like a faucet being slowly tightened, systematically reducing the flow of new coins into the world. Roughly every four years, the reward for mining a new block of transactions gets slashed in half.

This built-in scarcity is what gives Bitcoin its hard-money properties. It ensures the creation of new BTC slows down exponentially, preventing any sudden supply shocks and giving the network’s economic incentives time to shift. This controlled schedule is the engine behind Bitcoin’s deflationary nature.

The Halving: A Deliberate Slowdown

The halving is the cornerstone of Bitcoin’s monetary policy, and it happens like clockwork every 210,000 blocks. Since the network targets a new block every 10 minutes on average, this works out to roughly four years between each event.

Here’s a look back at how it has unfolded:

- 2009 (Genesis): The initial block reward was a hefty 50 BTC.

- 2012 (First Halving): The reward was sliced to 25 BTC.

- 2016 (Second Halving): It dropped again to 12.5 BTC.

- 2020 (Third Halving): The reward became 6.25 BTC.

- 2024 (Fourth Halving): Most recently, it was reduced to just 3.125 BTC.

This process will continue, with each halving chopping the reward into smaller and smaller fractions until it eventually hits zero. It’s also why, even though the final coin is over a century away, the overwhelming majority of all Bitcoin is already circulating. As of today, over 93% of the total supply is already out there, leaving a tiny fraction to be mined over the next 115+ years.

Why the Year 2140?

The final satoshi—the smallest unit of a Bitcoin—is projected to be mined around the year 2140. This isn’t some arbitrary date; it’s the natural conclusion of the halving cycle. As the block rewards diminish, the time it takes to mine the remaining slivers of Bitcoin stretches out dramatically.

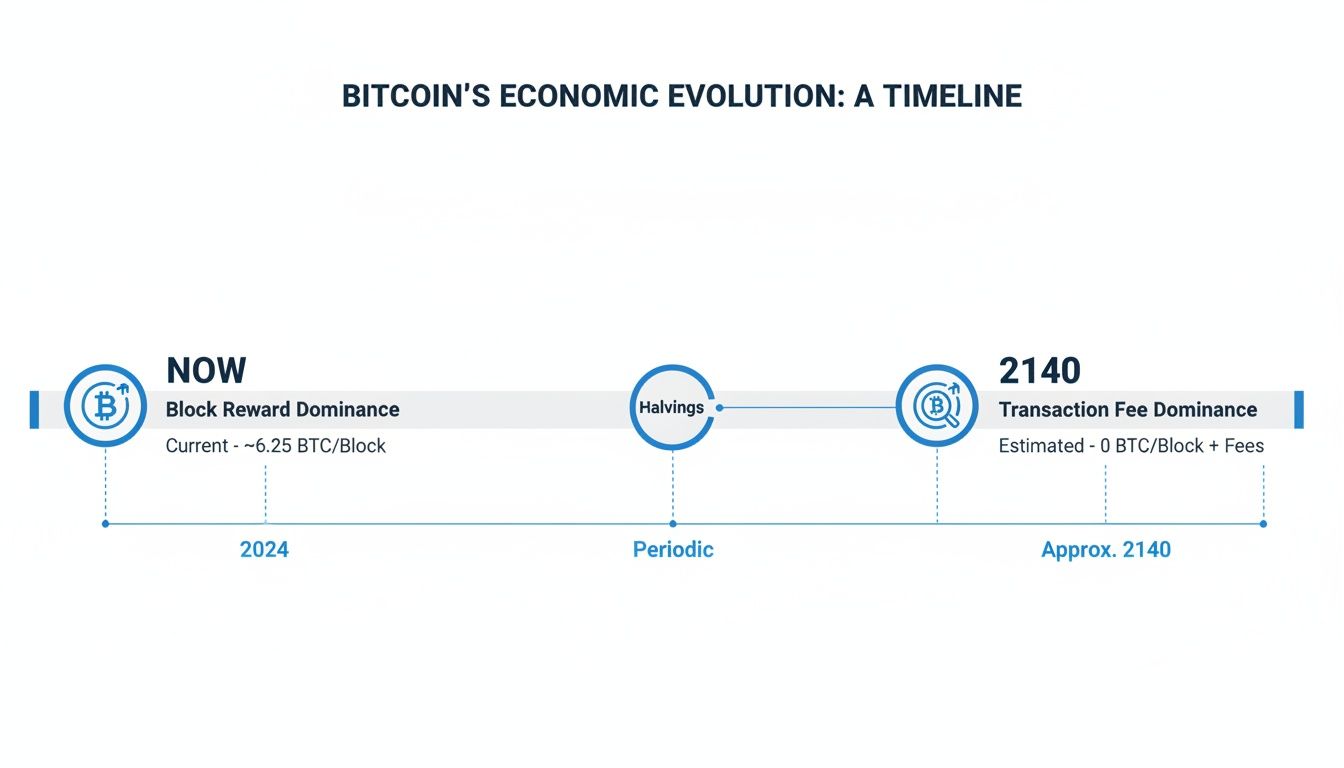

This timeline isn’t just about dates and numbers; it maps out Bitcoin’s long-term economic evolution. We’re moving from an era where the block subsidy is the main prize to a future sustained entirely by transaction fees.

As the visualization shows, this is a planned, methodical handover. The system is designed for fees to slowly but surely become the primary incentive, giving the entire ecosystem—from solo miners to massive Bitcoin mining pools—decades to adjust their business models.

The main point: The countdown to 2140 is less about a final, dramatic endpoint and more about the ongoing transition that secures Bitcoin’s future. The predictability of this schedule is a core feature, providing a stable foundation for a long-term, sustainable security model.

The Great Miner Pivot: From Block Rewards to Transaction Fees

The entire economic model for Bitcoin mining is built on a slow, deliberate, and profound transformation. Right now, miners have two ways to make money: the block reward (brand new bitcoin) and the transaction fees users pay. But the system was always designed for this balance to eventually tip completely in one direction.

As the pre-programmed “halving” events cut the block reward in half every four years or so, transaction fees have to rise to fill the revenue gap. The end of the block reward isn’t a cliff edge; it’s a graduation, where the network’s security has to stand on its own two feet, funded by its actual economic utility.

A Transition Proven by History

You can think of each halving as a live stress test for the mining industry. These events force operators to become hyper-efficient just to stay afloat on smaller rewards. And what history shows us is that the network is incredibly resilient.

After the first halving on November 28, 2012, the hash rate took a small, brief dip before rocketing to new all-time highs. We saw the same pattern play out after the 2016, 2020, and 2024 halvings. Miners adapt.

Fast forward to 2140, and miners will rely entirely on transaction fees. Today, block rewards still make up the lion’s share of income, but fees are becoming a much bigger piece of the pie. This evolution is critical, and you can find a detailed analysis on what happens when all bitcoins are mined that digs deeper into these future incentives.

What Drives the Fee Market?

Bitcoin’s long-term security hangs on one thing: a healthy and competitive “fee market.” It’s a market that runs on the timeless principles of supply and demand.

- Supply: The supply is the finite space inside each Bitcoin block. Think of it like digital real estate—there’s only so much transaction data that can fit.

- Demand: The demand comes from everyone who wants their transaction processed. Those who need it done quickly are willing to bid up their fee to get a miner’s attention.

When the network is busy, the demand for that limited block space skyrockets, driving fees higher. When things are quiet, fees fall.

From Subsidy to Pure Utility

This pivot marks a fundamental change in how Bitcoin’s security gets paid for. It’s moving from a system financed by a temporary, controlled inflation (the block reward) to one paid for directly by the people who use the network.

| Incentive Model | Primary Funding Source | Economic Driver | Long-Term Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current (Subsidy-Dominant) | Block Rewards (New BTC) | Bootstrapping network security | Wide distribution and adoption |

| Future (Fee-Only) | Transaction Fees (Existing BTC) | Demand for block space | Self-sustaining security |

In summary: This transition is essential because it perfectly aligns the miners’ incentives with the network’s usefulness. In a fee-only world, miners profit most when Bitcoin is most useful and in high demand, creating a powerful feedback loop for a thriving ecosystem.

How Bitcoin Stays Secure Without New Coins

When the last bitcoin is finally mined, what keeps the whole thing from falling apart? If there are no more new coins to reward miners, what stops a well-funded attacker from taking over?

The answer is baked into Bitcoin’s economic design. The network is built to transition from a security model paid for by inflation (new coins) to one funded entirely by its users through transaction fees.

The Security Budget: From Subsidy to Service

Think of Bitcoin’s security as having a “security budget”—the total amount of value (in BTC) that miners earn for their work. Right now, that budget is a mix of the block subsidy and transaction fees.

Once the subsidy hits zero, that budget will be 100% fees. The core idea is that a healthy, competitive market for block space can—and must—provide enough revenue to keep miners honest and online. For this to work, people must find the Bitcoin network useful enough to willingly pay for their transactions.

The Power of a Competitive Fee Market

A fee-only security model isn’t just a hopeful theory; it’s a raw market of supply and demand. Miners are rational economic actors. They will always prioritize transactions offering the highest fees to maximize their profits. This creates a natural auction for block space.

Of course, this raises a valid concern: what happens if transaction volume plummets? If demand for block space dries up, fees could collapse, making mining unprofitable and leaving the network vulnerable. This is a real risk, but one the ecosystem is already working to solve.

The bottom line: Bitcoin’s long-term security doesn’t rely on creating new coins. It relies on the network’s ongoing utility, which fuels a fee market robust enough to pay for its own protection.

How Scaling Solutions Actually Help

It might sound counterintuitive, but technologies designed to move transactions off the main blockchain could become a primary driver of on-chain fee revenue. The Lightning Network is the perfect example. It allows for tiny, instant payments off-chain that are periodically settled in a single, larger transaction on the main Bitcoin blockchain.

It’s like running a bar tab. Instead of swiping your card for every single drink, you settle up with one larger payment at the end of the night.

Here’s how it helps secure the network:

- Creates Consistent Demand: The Lightning Network bundles thousands of tiny off-chain payments into larger on-chain settlement transactions. This generates a steady and predictable demand for block space, helping to stabilize fee revenue.

- Encourages High-Value Settlements: The main blockchain evolves into a premium settlement layer for high-value transfers and large-batch settlements. For these critical transactions, users are more than willing to pay higher fees for ultimate security.

This creates an efficient, two-tiered system where the main chain handles high-security settlements, generating substantial fees, while everyday payments happen on faster, cheaper layers. For newcomers, grasping this layered approach is a crucial part of the learning curve, which we cover in our guide to Bitcoin mining for beginners.

How the Future Fee Market Will Impact Users

Once the block subsidies are gone, what does a fee-only world mean for the average person? Will sending a few bucks to a friend cost a fortune?

The answer really depends on how the fee market matures. At its core, this market will be a classic tug-of-war between the fixed supply of block space and the demand from users. This tension will almost certainly lead to a natural split in how Bitcoin is used.

The Great Use Case Split

In a world driven entirely by transaction fees, not all payments will be created equal. The main Bitcoin blockchain is poised to become a premium settlement layer—a high-security vault for transactions where finality and trust are paramount.

You wouldn’t use an armored truck to deliver a pizza, right? But you would for gold bars. The main chain will evolve for similar high-stakes purposes.

This creates a functional divide:

- On-Chain Transactions: These will be for the heavy hitters—large, critical payments where a higher fee is just the cost of doing business securely. Think settling a real estate deal or a major corporate treasury transfer.

- Off-Chain Transactions: Your everyday spending, like buying coffee or splitting a dinner bill, will likely migrate to scaling solutions built on top of Bitcoin.

Scaling Solutions for Everyday Payments

The best-known example of an off-chain solution is the Lightning Network. This “Layer 2” technology enables nearly instant, incredibly cheap transactions that don’t need to be individually recorded on the main blockchain right away. Users can open private channels and transact back and forth, bundling all the small payments into a single, larger settlement transaction later. This is what makes small, frequent payments economically feasible.

In essence: Bitcoin is designed to evolve into a multi-layered financial system. The main blockchain will act as the ultimate court of settlement, while faster, cheaper layers handle the high volume of daily commerce.

Comparing On-Chain and Off-Chain Transactions

This table breaks down the fundamental differences between transacting on the main blockchain versus using a Layer 2 solution.

| Feature | On-Chain (Main Blockchain) | Off-Chain (e.g., Lightning Network) |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Use Case | High-value settlements, large transfers | Everyday payments, micropayments |

| Transaction Speed | Slower (10+ minutes for confirmation) | Instantaneous |

| Transaction Cost | Potentially high, based on demand | Extremely low (fractions of a cent) |

| Security | Highest possible level of security | Relies on the main chain for final settlement |

This evolution isn’t a bug; it’s a feature. It’s how Bitcoin can scale to a global user base without compromising the decentralization and security that make it valuable.

How Mining Operations Must Evolve to Survive

The end of the block reward isn’t some distant, abstract event for Bitcoin miners. It’s the economic endgame that’s already forcing the industry to adapt. When transaction fees become the only source of revenue, survival will hinge on a relentless pursuit of efficiency.

This shift is already driving a massive professionalization of the sector. Forget the old days of mining from a garage. Today’s successful operations are industrial-scale enterprises, constantly hunting for the world’s cheapest electricity.

The Unrelenting Drive for Peak Efficiency

When your profit margins are paper-thin, every fraction of a cent matters. This intense pressure will compel miners to innovate across every part of their business.

Three key areas will separate the survivors from the casualties:

- Hardware Advancement: A perpetual race for the next generation of ASIC hardware to squeeze the most hash rate out of the least amount of energy.

- Energy Sourcing: Locking in long-term, low-cost power agreements, often by co-locating with renewable energy producers.

- Operational Excellence: Fine-tuning everything from data center cooling systems to software that predicts fee spikes to build the most profitable blocks.

The takeaway for miners: The future isn’t just about having the fastest chips; it’s about building the leanest, most adaptable business imaginable.

Consolidation and the Rise of “Super-Pools”

As competition gets fiercer, the mining industry is almost certain to consolidate. Smaller, less efficient miners will struggle to keep up with large operations that can leverage economies of scale.

This trend will also reshape mining pools. To maximize earnings in a fee-only world, pools will need advanced strategies:

- Sophisticated Fee Prioritization: Using complex algorithms to build blocks packed with the most lucrative transactions.

- Transaction Acceleration Services: Offering “express lane” services for users willing to pay a premium for urgent confirmation.

- Diversification of Services: Branching out into other business lines, like financial or custody solutions.

Miners can use tools like a detailed crypto mining profitability calculator to run the numbers on different future scenarios and stay ahead of the curve. Ultimately, the transition away from block subsidies is a survival-of-the-fittest test that will permanently redefine the mining landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Here are answers to some of the most common questions about what happens after the last Bitcoin is mined.

1. Will the Bitcoin network shut down when all coins are mined?

No. The network’s ability to process transactions is independent of new coin creation. It will continue to run, with miners being compensated entirely through transaction fees instead of block rewards.

2. Is the 21 million Bitcoin limit set in stone?

Practically, yes. While it’s technically software, changing the supply cap would require near-unanimous agreement from the entire global community. Since Bitcoin’s value is based on its scarcity, any attempt to inflate the supply would be rejected by the vast majority of users, miners, and developers.

3. What happens to all the lost Bitcoin?

Millions of bitcoins are permanently lost on old hard drives or in wallets with forgotten passwords. These coins are effectively removed from the circulating supply forever. This doesn’t change the 21 million hard cap, but it does make the remaining, usable coins even scarcer, reinforcing Bitcoin’s deflationary nature.

4. How will transaction fees be determined in the future?

Transaction fees will be determined by a free market based on supply and demand. The supply is the limited space in each block, and the demand comes from users wanting their transactions confirmed. During times of high network usage, fees will rise. During quieter periods, they will fall.

5. Will my Bitcoin wallet still work after the last bitcoin is mined?

Yes, absolutely. The end of the block subsidy is an economic shift that affects miners, not the fundamental way users interact with the network. Your wallet will function exactly as it does today for sending and receiving Bitcoin. The only change you might notice is that the fee you choose to pay will have a more direct impact on confirmation time.